We take so much for granted. Rightly or wrongly, we believe we are invincible and our coping ability will fix anything. Throw a problem at us and we will find a cure. Tell us a species is nearly extinct and we’ll pull off an 11th hour rescue. We’ll rush through legislation. We’ll scour funding. We’ll create a habitat to ensure survival and change destiny.

We flourish on urgency and excel on adrenaline.

We believe it is so because we have done it. We did it with alligators in Florida, once threatened, now so plentiful that we license hunters to kill and control the population. We are doing it with sharks in The Bahamas and to a lesser extent with the threatened Green Turtle, once on the international list of critically endangered species, now regenerating since being protected by law in The Bahamas in 2009.

But there was one species that slipped through our fingers, the wild horses of Abaco. Called Spanish Barbarys, the short, stocky horses with massive necks and thick, powerful legs were officially recognised as descendants of Spanish equine royalty. Their ancestors came by sea to The Bahamas more than 500 years earlier, brought by Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Conquistadores, sharing cargo space with seeds, plants, cotton, tools, food stuffs.

No one can explain why the wild horses thrived in Abaco but thrive they did. That is, until the very last one, a mare named Nunki, died in July 2015. An entire royal population extinct -- except for the sliver of DNA from Nunki. Reportedly kept in protective custody in Miami, could Nunki’s DNA reignite a royal population by cloning?

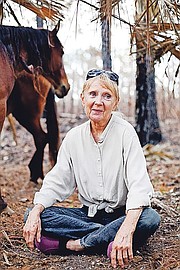

I first came across the fascinating story of the wild horses of Abaco when writing for a travel magazine more than a decade ago. The fascination was triggered not so much by the horses themselves, but by the dedication of a tiny woman, all of 5’ 2”, who was trying to save the last few still alive. A New York photographer who had visited the Abacos many times, Milanne ‘Mimi’ Rehor was so taken by the beauty of the wild horses she’d caught on film she eventually relocated to the island, forging a new life with renewed purpose, to preserve the species. In her late 60s when I interviewed her, in boots and denim working out of a converted 20-foot container, she was still filled with hope. For more than 20 years she would continue to dedicate her talent, her time, her heart to the declining, powerful breed, outliving the last of the horses she tried so valiantly to save.

Milanne ‘Mimi’ Rehor became to Abaco’s wild horses what Jane Goodall was to the wild chimpanzees of Tanzania.

Though there are differing versions of what caused the demise of the breed, loss of habitat and chemical run-off from poisonous fertiliser following torrential rains seem to be contributing factors. Numbers of the stock rose and fell through the centuries, soaring in the 1800s following the importation of new stock from Cuba for Abaco’s logging industry. When the industry switched from labour by beast of burden to tractor for hauling the logs in the 1940s, the horses were set free and reportedly ran wild, galloping and reproducing in all their newfound freedom. Tragically, a young child died while trying to ride one and the local population went on a tear, destroying as many as they could. All but three were killed off. By the mid-60s, the population rebounded to about 35. Slowly, failing to reproduce in any numbers, they dwindled and when Nunki died in Mimi’s arms on that July day in 2015, moving tributes poured in. The death made international news.

If it had not been for the photographer who made a boat in the harbour her home and the capturing of the wild horses of Abaco her passion, another important part of Bahamian history would have been lost forever. Can Nunki’s DNA launch another generation of wild horses? We don’t know yet, some say it is unlikely, but thanks to a tiny woman who wore a camera around her neck and a love in her heart we have images of what we lost and a destiny we were not invincible enough to change.

Redevelopment of Arawak Cay is either a great idea or a disaster in waiting

During his budget contribution on Wednesday, Prime Minister Hubert Minnis revealed a development bombshell that took just about everyone outside the inner circle by surprise. He called for a complete redevelopment of the area between The Pointe and Arawak Cay, encompassing what is now known as Junkanoo Beach, Long Wharf and Fish Fry.

The plan is certainly ambitious, not a band-aid on a cancer. That’s to its credit. It also recognises that the millions of cruise passengers who visit Nassau, many of them repeat visitors, find the city wanting and the beaches either hard to get to or a far cry from what the brochures promised. Also to his credit. We have always treated our cruise passengers as second class citizens, not even providing for them public rest rooms downtown nor protecting them from the dozens of hasslers and hustlers when they dare to disembark and make their way through the area around Festival Place besieged by everyone with a service, a basket, a t-shirt of a jar of peppers to sell.

But there are real concerns that must be addressed if a sudden entertainment district is to succeed. First, entertainment districts are most often organic. They start with a few people in a band or a guitarist on a corner, then a saxophone player sets up on another corner, and a few jazz nights happen and the district grows, fueled by reputation. Creating a series of buildings and filling them with entertainment is risky business. It could work, but there is definitely a maturing that will have to take place.

While I applaud the idea of a boardwalk and hope it will include a bike path, jogging trail and fitness stops, what is of greatest concern (once architecture is attractive) is protected view of the harbour. Long Wharf has always been one of those special places where in the midst of the busiest day we know we are privileged because the water is right there. It is as if we can breathe it in.

The connection between Bahamian waters and Bahamians runs so deep and is so powerful it is hard to even put into words. It just is. it’s real and it’s important.

In too many places, the sight of the sea has been stolen from us and given to another. Please, please do not let that happen at Long Wharf and the eastern end of Arawak Cay. Build a boardwalk, create activities, add attractive lighting and security and have a concert area, but keep the view of the water for those of us to whom it is our daily bread and our lifelong emotional nutrition. And whatever the plan, please remember the promise of transparency. The more people are involved, the more they are able to contribute, the greater the supporter of a plan they become.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID