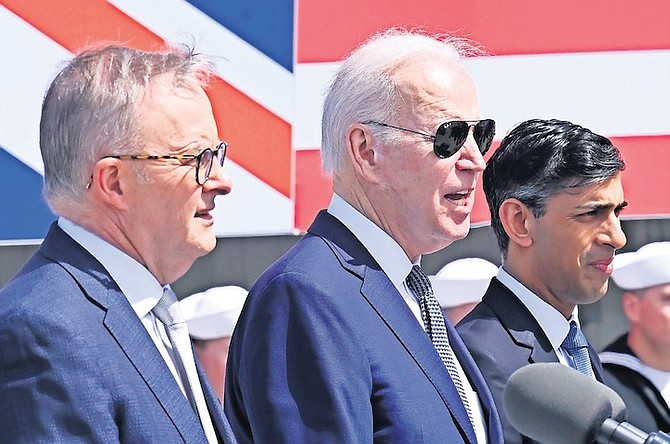

BRITAIN’s Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, right, meets with US President Joe Biden and Prime Minister of Australia Anthony Albanese, left, at Point Loma naval base in San Diego, US, Monday March 13, 2023, as part of AUKUS, a trilateral security pact between Australia, the UK, and the US. Photo: Leon Neal/AP

WITH the publicity surrounding last week’s San Diego meeting about the AUKUS agreement, I wonder how many people will have recalled one of US President Biden’s famous gaffes. This was at the virtual press conference in September, 2021 - attended by Biden and the then Australian and British prime ministers, Scott Morrison and Boris Johnson - announcing this far-reaching defence and security alliance between the three countries when Biden could not remember Morrison’s name and in addressing the press called him simply “that guy down under”.

At last year’s press conference, the US president announced this ground-breaking trilateral agreement which was to be called AUKUS. Under its terms, the three countries would co-operate in the development of the first nuclear-powered - but without nuclear weapons - fleet for the Australian navy, making it only the seventh country in the world to have the powerful deterrent of such submarines. It would also substantially increase the size of Britain’s own nuclear-powered submarine fleet.

The impetus for this was security concerns about China’s increasingly aggressive moves and military expansion in the South China Sea and the consequent need to defend the West’s interests in the Indo-Pacific region.

For Britain, the AUKUS pact fitted with the government’s foreign policy review published in March of the same year which recognised that while the US remained the UK’s most important strategic ally and partner – and NATO was the bedrock of defence and security in the Euro-Atlantic sphere – there was a need partially to shift Britain’s focus towards the Indo-Pacific region which was becoming the geopolitical centre of the world, with countries such as India, China, Japan and Australia among others home to a quarter of the world’s population and making up 40 per cent of global GDP.

Unsurprisingly, China reacted strongly to this announcement in 2021 about AUKUS, saying that the pact risked severe damage to regional peace and intensification of the arms race. Now, eighteen months later, details of the agreement have been released at the San Diego meeting between Biden and the current Australian and British premiers, Anthony Albanese and Rishi Sunak. AUKUS will be based on a British design and will be partly manufactured there as well as in Australia, with the first submarines seaworthy from the late 2030s. China has strongly opposed the agreement once more in the strongest language since Beijing’s reaction to the ill-advised visit by the US political leader Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan last summer.

For their part, the AUKUS partners say that the agreement will contribute to “global security and stability” and, in the words of the US president, it is aimed at bolstering peace in the region. The joint statement at San Diego stressed that the three nations have traditionally stood “shoulder to shoulder with other allies to help sustain peace, stability and prosperity around the world, including in the Indo-Pacific” and that there was a continuing need to protect freedom, human rights, the rule of law, the independence of sovereign states and the rules-based international order.

Albanese pointed to the economic benefit to his country of building the submarines partly in Australian shipyards, adding that this marked the “biggest investment in Australia’s defence in all of its history”. But, despite recent differences about the origin of the COVID-19 virus, he also wanted good relations with China as Australia’s biggest trading partner.

Sunak spoke of the pressing need to shore up stability in the region while Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine together with China’s growing assertiveness and the disturbing behaviour of Iran and North Korea all created disorder, division and danger in a troubled world. He said that China posed an “epoch-defining challenge” to world order. Britain could not be blind to this while also wanting to engage with China as the “sensible and responsible thing to do”. The British Prime Minister pledged meanwhile to increase defence spending by some $6 billion over the next two years.

Overall, the AUKUS project has sparked fresh debate about how the West got it wrong in its earlier assessment that economic liberalisation in China would lead to an opening up of society and greater political freedom. As Western multinationals set up joint ventures in China and the standard of living rose, the reasoning was that the Chinese Communist Party might loosen its grip and allow modest democratic reforms. But it has not worked out like that. As China has become an economic giant and developed a military force to be reckoned with, the CCP has tightened its grip on the country; and the experts maintain that, while it does not want war with the West and is willing to engage with the rest of the world as long as that is on its own terms, China is intent on challenging the US for world domination.

Finalisation of the AUKUS pact at San Diego has been described as a projection of power and collaborative intent by old democracies coming together to counter a new and growing adversary in the shape of China. There are now high hopes that this is an alliance that will last, not only because of the serious level of trust in sharing sensitive technology but also because of the long timelines for construction of the submarines. Given the scope and length of the project and the heavy investment, the commitments made will surely be hard to break.

US PRESIDENTS BURNISH THEIR IRISH CREDENTIALS

FOR DEVOTEES of US TV channels, it was hard to miss coverage of the visit to the White House of Ireland’s Prime Minister last Friday when President Biden celebrated St Patrick’s Day with him; and nobody could have missed the President showing off proudly the water in the White House fountains which had been turned green in celebration of Ireland’s National Day.

As the only Catholic occupant of this famous building apart from John F Kennedy, Biden is known for regularly making reference to his Irish roots and identifying himself as Irish-American. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that US presidents tend to emphasise their “Irishness” and burnish their Irish credentials even if their links with the “Land of the Leprechauns” have been found to be tenuous. Former President Clinton, in particular, was known for claiming Irish roots – despite the lack of evidence to back that up.

There are said to be as many as thirty million people in the US who identify as Irish and many claim that Irish migration over the years has been a vital part of the American saga. Irish nationalism runs high and the polls suggest that a majority of Americans, if asked, would support a united Ireland. US presidents tend to indulge such views, though in practice such a stance has little impact on US-UK relations. Generally, across the political spectrum the US has supported peace and prosperity in Northern Ireland for decades and there has been involvement in the peace process there, though not always without controversy.

Biden himself has taken a close interest in this process. But the evidence shows that he and his colleagues have tended to misunderstand the facts about the Northern Ireland Protocol post-Brexit. That said, the good news is that he has indicated his intention to attend the 25th anniversary celebrations in April of the 1998 Good Friday agreement. The US claims to have helped broker this agreement to bring an end to decades of sectarian violence – and, for Biden, a visit to Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland would surely be a symbolic return to his much touted Irish roots.

WILL PUTIN EVER HAVE TO ANSWER FOR WAR CRIMES?

IT WAS not hard to predict what would hit the headlines last week. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued an arrest warrant for Russian president Vladimir Putin. The court alleges he has been responsible for war crimes in Ukraine. This has come as no surprise but the timing is unexpected. Reportedly, the ICC thought of keeping the warrant secret because of concern it might harden Putin’s attitude and finally close the door on any prospect of peace negotiations to bring the war to an end. The conflict has reached a relative stalemate and such talks to stop the fighting and secure the withdrawal of Russian troops cannot be ruled out.

However, the court, which has been investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity in Ukraine as far back as 2013 - a year before Russia’s annexation of Crimea - states it is now going public in the hope that this might deter further such war crimes and stop them altogether from being committed, though many people regard that as naïve wishful thinking.

Russia does not recognise the ICC or its jurisdiction and has already dismissed the warrant as “outrageous”. The Kremlin regards it as meaningless and it is unlikely to have any effect on the course of the war. It is also unlikely that the warrant could even be successfully served on Putin. But it might be worth examining briefly some of these issues today.

The ICC says it has reasonable grounds to believe Putin committed the criminal acts directly as well as working with others. The court has focused its claims on the unlawful deportation of children from Ukraine to Russia, and a UN report has condemned these forced deportations as “violating international humanitarian law and amounting to a war crime”. Russia’s commissioner for children’s rights, who has spoken openly about indoctrinating Ukrainian children taken forcibly to Russia, is also wanted by the ICC for the same crimes. In addition, Russian troops have been accused of thousands of abuses against civilians and, according to evidence from Ukraine itself, more than 62,000 war crimes have been recorded including the deaths of as many as 450 children.

There have been countless attacks on civilian infrastructure so that the UN believes there is sufficient evidence to accuse Putin for these according to the rules of warfare which are set out in international treaties, notably the Geneva Conventions. Furthermore, while the US played a central role in the creation of the ICC, it is not a signatory to it. But President Biden has said that the court is right to issue an arrest warrant for Putin and his Vice President declared at the Munich Security Conference in February that the US formally accused Russia of crimes against humanity in Ukraine.

So, what might happen next? The issue of an arrest warrant for Putin is likely to be no more than the first step of a lengthy process. The ICC was established in 2002 and 123 countries are signatories to it. The court lays down that it is the duty of any state to exercise its own criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes. So it will only intervene when a state is unable or unwilling – as, in this case, Russia - to carry out an investigation and prosecute perpetrators. Ukrainian courts have already prosecuted a Russian soldier who was jailed for life for shooting an unarmed civilian, and other cases are going on with no doubt more to follow. But, to all intents and purposes, Putin himself faces no prospect of being arrested unless he travels to one of the ICC’s signatory countries or he is ousted from power.

As for the wider effects of the arrest warrant, it is already being seen as a firm and unequivocal signal from the international community that what is happening in Ukraine is against international law. The ICC has revealed the extent of opposition to the Russian invasion. Some commentators are now saying that this should be a wake-up call for countries not in the Western alliance and who have failed to condemn Russia’s invasion; and it could bring about a change of attitude in such countries in dealing with a suspected war criminal and wanted man. Moreover, there is now mounting pressure internationally to set up a one-off Nuremberg-type tribunal to try crimes against humanity and prosecute the crime of aggression. It is clear that, although holding Putin and his colleagues to account for war crimes will take time, the ICC action over an arrest warrant will be widely welcomed as a step in the right direction.

Comments

Porcupine 1 year, 1 month ago

My God. What does this guy read? Assertive China? The US has nearly 800 military bases throughout the world. China, two. The US has encircled Russia with nuclear weapons. Mr. Young, get your head out of your butt. Do you have any truly educated friends?

LastManStanding 1 year, 1 month ago

China is much more dependent on economic soft power than the US; that, plus the fact that most of their neighbors (aside from N Korea) hate them, means they really haven't had the chance to put a whole bunch of military installations overseas. That being said, I agree with you that TPTB in the West are going to force a war with Russia and China soon enough; they are giving Russia in particular no other option, and China is looking at the Ukraine situation and anticipating the same playbook with Taiwan.

Sign in to comment

Or login with:

OpenID